Linguaviagem: Corresponding with Augusto de Campos

tradução para o português

I first met Augusto de Campos in July, 2016 when I traveled to São Paulo to see a major retrospective of his art and poetry. At the time, I was in the midst of preparing an exhibition on concrete poetry at the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles. My exhibition highlighted the Noigandres group of Brazilian concrete poets, whose work was widely represented in our collections, but, surprisingly, not well known in the United States. During the course of completing my exhibition work, Augusto became an extraordinarily generous correspondent. He translated the Brazilian poetry in my exhibition, sent me commentary on his poetry, and provided me with state-of-the-art digital projections which enabled us to screen his visually captivating poetry on a large gallery wall with vocal accompaniment.

Our most recent correspondence, which is the focus of this essay, developed over the course of work on my forthcoming publication, Concrete Poetry: A 21st-Century Anthology (Reaktion Books, October, 2021). Augusto is one of three poets who receives highest attention in the anthology — along with Ian Hamilton Finlay and Gerhard Rühm. I argue that their poetry transformed the genre, each in distinctive ways. Augusto has been an especially marvelous interlocutor, because he is interested in engaging on all levels: the scope and geographical purview of concrete poetry; poetic structure; typography, printing, and fonts; political message; the relationship of form to content. I’m keen to share his letters because they reveal his poetics. In addition, you will appreciate his kindness, his boundless imagination, his erudition in literature, music, and the visual arts, his astonishing linguistic gifts, and his interest in theorizing about concrete poetry.

I will start with Augusto’s response to a question I posed about the inclusion of Argentinian concrete poets in my Anthology (March 19, 2018):

Fig. 1: Olho por olho. 1964. Augusto de Campos

There were no Argentine poets in the first decade of 1950. Only in 1967 did the poet of La Plata, Eduardo Antonio Vigo, become aware of concrete poetry.1 He was publishing since 1962, in his hometown, a magazine called Diagonal Cero, dedicated to experimental poetry. In 1967 he contacted us and published Issue No. 22, with my poem on the cover, and an extensive article by Haroldo [de Campos] on the new poetry. From then on, his magazine, which had a few more numbers until 1969, began to publish texts of visual poetry more intensely. We lost contact with him, because the visual poetry he practiced did not interest us, since we were inclined not to dispense with the semantic level even in non-verbal experiments such as “Eye for Eye”, “Profilograma Pound / Mayakovsky”…

Fig. 1 shows Augusto’s popcretos poem, Olho por olho (Eye for Eye), a non-verbal poem which communicates both visually and semantically through the tower of single eyes, female mouths and, at the very top, traffic signs (“Danger”, “One way”, “Right turn only”), all conveying a sinister message of surveillance. By incorporating this “semantic level”, which he argued played little role in Argentinian visual poetry, Augusto invoked the linguistic dimension which James Joyce made part of his “verbivocovisual”: In a given concrete poem, the visual, sonic and semantic dimensions of a poem cannot be separated: form equals meaning.2

Augusto and I had a longer correspondence between May 1 and May 6, 2018, over the structure of his poem, Acaso (Chance), written in 1963 (Fig. 2). Recalling that he wrote this poem at a time when he was particularly focused on the use of chance in poetry, Augusto calls attention to the influence of Stéphane Mallarmé (especially Un Coup de dés), the indeterminacy of John Cage, and the aleatoric method of Pierre Boulez. He continues:

It occurred to me to use the very word “acaso” (chance) as a theme, and I tried to compose an iconic text only with its anagrams.3 I finally decided to align all the anagrams of “acaso” in alphabetical order, and then reverse that order, so that the word “acaso” did not appear in the first stanza. Luckily, the anagrammatic vocables did not form any vernacular word, only suggesting the word “caos” (chaos) in “acaos” (which evokes “no chaos”) and “caaos” (which gives a hint of chaos). [see both in the final stanza]

Fig. 2: Acaso. 1963. Augusto de Campos

First stanza source:

aacos

aacso

aaocs

aaosc

aasco

aasoc

Appears in reverse, from right to left:

socaa

oscaa

scoaa

csoaa

ocsaa

cosaa

The second block of six lines follows the alphabet, beginning with “acaos”, working its way down to “acsoa”, then reversing the order, as follows:

Second stanza source:

acaos

acaso

acoas

acosa

acsao

acsoa

In reverse:

soaca

osaca

saoca

asoca

oasca

aosca

Referring to the second text block, Augusto explained that were he to have simply presented the anagrams in alphabetical order, “acaso would appear in the second stanza and would be easily discovered. I wanted to make the deciphering more difficult, to increase the timing, give a breath to the reading, and for this purpose I had the idea of inverting the order of the anagrams.” Intuitively, Augusto followed the “factorial formula for permutation”: given five letters, with two repeats (the “a”), he mapped out the possibilities as follows: 5 × 4 × 3 × 1 = 120, divided by 2 = 60.

The result was a poem comprised of ten blocks, each six lines long. Due to the use of every possible permutation of the letters “acaso”, the word that it spells has to appear once and does so in the eighth text block (fifth line). “Acaso” is the only legible word; all the rest are non-signifying anagrams.

As we study Augusto’s poem more closely, we are struck by the contrast between the idea of “chance” and Augusto’s rigorous procedure for releasing the anagrams so as to avoid legibility and repetition. The influence of John Cage’s famous piano composition, Music of Changes (1951), his first to utilize chance operations in composing a work, is notable. Cage’s instructions call for negating the self, that is, removing the self from choice, and introducing chance by tossing three coins twice, obtaining a number, finding its corresponding hexagram in the I Ching Book of Changes, and looking up the corresponding cell in one of Cage’s three charts (sounds, durations, and dynamics). In Cage’s terminology, “chance” refers to the use of some sort of random procedure in the act of composition.4 The permutation and ordering in Augusto’s Acaso is generated deterministically, not randomly, from five letters. Since the ordering principle is sufficiently complicated, the structure is not immediately apparent. Both Cage and Augusto establish rules which allow them less control over the outcome. Yet chance, clearly, does not mean lack of rigor!

Fig. 3: Linguaviagem. 1975. Augusto de Campos

Augusto and I pursued a different line of exchange on the subject of reproducing his poetry in its original published appearance, which he took to mean printing, font and format. Our correspondence (July 2, 2019) focused on his Linguaviagem (Tongue Voyage) (1967–70) (Fig. 3).

I had been impressed by the large cube version of this poem made for the Brighton Concrete Poetry Festival in 1967 and consisting of heavy blue and green fonts. I assumed that Augusto was responsible for this version, but his letter indicated otherwise. Comparing the Brighton poem to his original, he wrote:

The English version, made in the Brighton exhibition, from my prototype, is more impressive in its colors and dimensions. But it departs somewhat from my original, which is more orthodox, in black and white, with less heavy letters and a more harmonious formal relationship between the letters and the format of the page. The glossary printed inside the poem facilitates understanding… given the difficulty of the language. However, it has the disadvantage of interfering with the composition. It seems to me that the glossary, which I had provided, might be better published separately…

In fact, beyond the individual meanings of words, the poem, unfolded, suggests two phrases:

LINGUAVIAGEM (neologism) voyage through language

VIALINGUAGEM (neologism) way through language…

as in French, LANGUE, LANGAGE,

In Portuguese LINGUA is a synonym for LANGUAGE

this being the most generic word”

LINGUA — “language”, but also “tongue”

The poet invites the reader to come with him on a voyage via language.

VOYAviaLANGUAGE? LANGUAviaVOYAGE?

No satisfactory translation. We have lost the passage of VIA, common to both languages.

Augusto’s attempt at an English-language translation of his poem illustrates just how difficult it is to capture his neologisms, as well as the multiple Portuguese words for “language” (lingua, linguagem), and the embedding of words within words. The truest display might reveal the two neologisms, each on an accordion fold, as presented in the Rever exhibition.

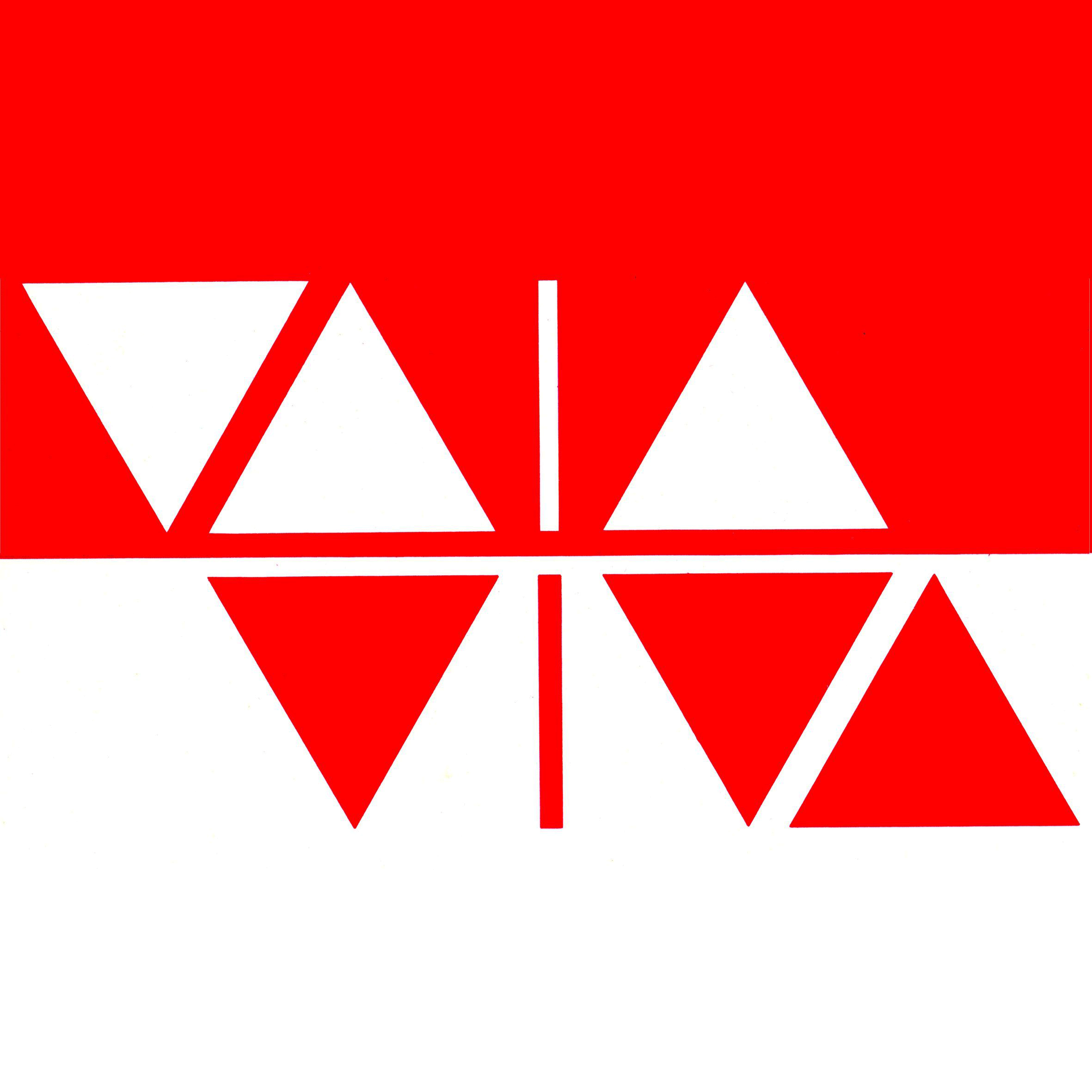

One of Augusto’s most remarkable poems had its source in autobiographical events. Viva Vaia (Hurrah / Hissing) owes its name to a performance by Caetano Veloso in São Paulo on September 15, 1968, when nationalist leftist students booed him. In a letter sent me on August 20, 2019, Augusto recounted: “It was a very peculiar incident that was like an unforeseen happening. Caetano continued to sing among the boos and exploded in a fiery speech that said: “You don’t understand anything. You are fighting the old men who died yesterday.”

During the “traumatic events” that followed, Caetano and fellow singer and songwriter Gilberto Gil were imprisoned, then sent into exile in London in July 1969. They did not return to Brazil until January 1972.

Fig. 4: Viva vaia. 1972. Augusto de Campos

Following a family trip to Teotihuacan, Mexico in December 1971, where he saw the Pyramids of the Sun and the Moon, Augusto began to make a “minimalist poem”. Intrigued by the “A” and the “V” in the word “Carnaval” (it was February 1972), he thought of creating a poem in which the words “Viva” (Hurrah) and “Vaia” (Hissing) would confront one another. He dedicated the poem to Caetano and described it to me as a “public response that encompassed us all, the “concrete poets” who lived under intense criticism, booed by all, like him.” (Fig. 4)

The two words (Viva Vaia), pressed into a one-unit ideogram, hold opposite meanings, yet share the same letters and a phonological kinship (two-syllables, initial v, closing a). The triangular forms evoke the pyramids of Mexico. Astonishing in its compression and abstraction, Viva Vaia did not appear in print until 1973-74 in the magazine Navilouca (Crazyship), with the title, Monument to the Boo. Augusto published it next to a photograph of Caetano Veloso holding the “object poem” in his hands.

As you can see from my accounts of our correspondence and from the commentary Augusto provides on his poetry, he has been an invaluable interlocutor. I’d like to close with a brief segue to his SOS, which began as a concrete poem in 1983 and evolved into a multi-media digital animation. Having seen SOS in its latest digital incarnation at the exhibition Rever (2016), I was inspired to make it the capstone of my Getty exhibition by projecting it on the final gallery wall (2017). Augusto’s pursuit of the “verbivocovisual” culminates in the sounds, spoken voices, and ominous yellow-on-black palette of SOS. Indeed, this work epitomizes for me a trajectory of Augusto’s career. As a poet who turns ninety in February, 2021, he continues to unveil innovative and creative uses of technology to meet his synaesthetic ends. He is, I would argue, among the most inventive living poets in the world today. He is also a truly kind and generous human being.